May 11, 2017; Al-Monitor

As the civil war in Syria rages on, the conversation in other countries often turns to the nearly five million refugees who have fled the conflict. Though other nations have been hesitant to accept large refugee populations, it turns out they can actually be a boon to the economy.

Recent studies done on Syrian refugees in Turkey show that 78 percent of Turkey’s Syrian immigrant population, or 2.34 million people, would opt to stay in Turkey if they were allowed to do so. Turkey is classified by the World Bank as an upper-middle-income country with a population of about 78.6 million people, or about one-fourth that of the U.S.

Though nationalist and isolationist movements, such as have been sprouting in the U.S. and Europe in recent years, might bristle at the thought of 2 million permanently resettled Syrians, studies show that it would actually help the local economy. For every 10 percent increase in diversity, Al-Monitor calculations based on 50 years of population data showed a 2.1 percent rise in Turkish GDP per capita. Because of laws that limit the proportion of Syrians that Turkish companies can hire, immigrants often start their own companies, and this benefits the population at large; every one percent increase in Syrian companies’ capital brought a 0.2 percent increase to the average daily earnings of all registered laborers.

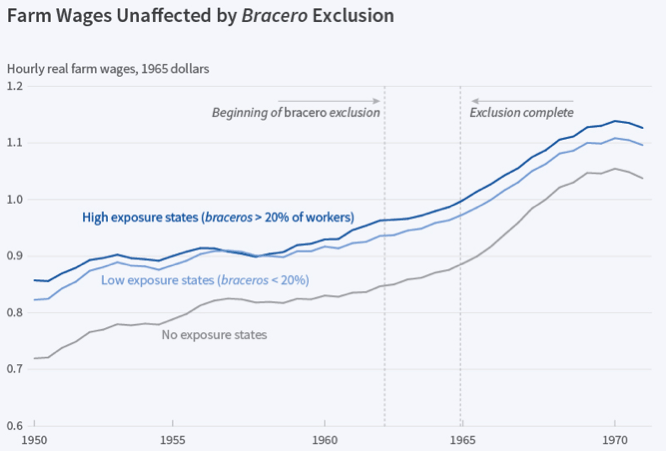

One of the popular arguments made by anti-immigrant activists is that they take jobs away from workers who are citizens of that country, but even where regulations like Turkey’s don’t exist, statistics often show that’s not true. For example, in the early 20th century, the U.S. allowed Mexican nationals into the country on temporary visas to do agricultural and other manual labor, through an agreement known as the Bracero Program. In 1963, the program was ended in the hopes that fewer available laborers would push agricultural wages up. Instead, farms invested in technology and there was no impact on farm labor wages.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The researchers compare labor market outcomes for native workers before and after exclusion of the Mexican workers in heavily affected, lightly affected, and unaffected states. They find that pre- and post-exclusion farm wages and farm employment were similar in states highly exposed to exclusion—which lost roughly one-third of hired seasonal labor—and in states with no exposure.

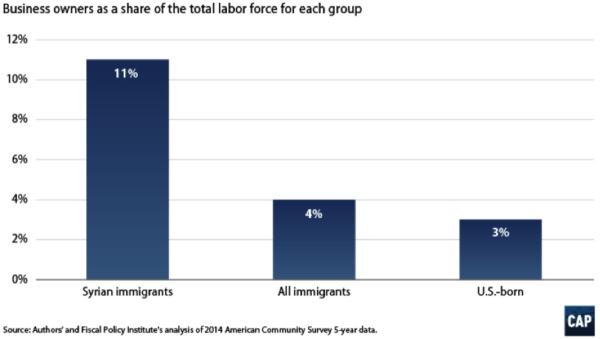

In fact, immigrants often create jobs. Syrian immigrants hold advanced degrees at more than twice the rate that native-born American citizens do, according to the Center for American Progress, and they start or own businesses nearly four times as often.

The Washington Post quoted David Dyssegaard Kallick, senior fellow at the Fiscal Policy Institute, as saying, “The United States accepts refugees on humanitarian grounds, not to improve the American economy. But, the striking success of Syrian immigrants in this country should give us some confidence that Syrian refugees can become integrated and successful here.”

So what does this mean for nonprofits? Some have already caught on to the idea that in addition to very important humanitarian reasons, there is an economic benefit to accepting refugees. Still, the conversation about refugees too often focuses on safety, even though statistics show—and as NPQ has previously reported—that Americans are more likely to drown in a bathtub than be killed by a terrorist, and crime rates in cities that protect refugees are lower than in ones that don’t.

Maybe it’s time for the conversation to focus not on how to minimize the damage, but how to maximize the benefits. Maybe nonprofits focused on economic growth and those focused on refugee advocacy and integration have more in common than we previously thought. When we say that we’re stronger as a country when we’re inclusive and open, it has real meaning, and there’s data to back it up.—Erin Rubin